Wildlife and animal poaching have been around for far too long, and honestly, normalised since we were kids – even if we didn’t realise it back then. Think about it…

How many of us grew up watching Cruella De Vil plot to skin dalmatians? Or Clayton in Tarzan, pretending to protect Jane while actually planning to poach gorillas? Or Percival C. McLeach in The Rescuers Down Under, who made poaching look like just another adventure?

These characters were obviously villains, but their actions were introduced to us so early and casually that we kind of just accepted them as part of the story. The message was there, sure, but we weren’t exactly encouraged to think about the real-world version of things like this – or our ability to do something about them. It was simply “how things were.”

All of that is changing. Today, awareness around poaching and wildlife conservation is growing fast. People are realising this isn’t just something that happens far away; it’s real, and we do have a say in it.

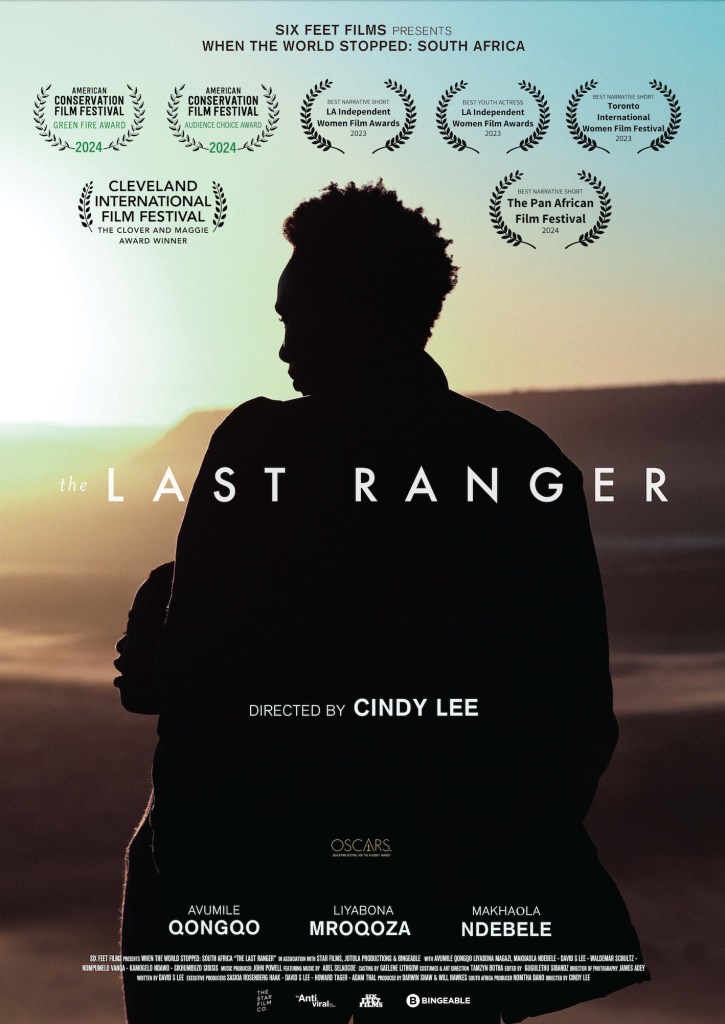

Enter The Last Ranger, a powerful South African short film that dropped last year and has earned an Oscar nomination. It’s a reminder that we all play a role in what happens to our wildlife. The question is: Which side of the story are we on?

“We all have a role to play in conservation – it just looks different for each of us.”

David S. Lee, actor and The Last Ranger filmmaker

The internationally praised film is rooted in truth and tells a deeply emotional story of loss, resilience, injustice, poverty, and how badly some governments have failed their people. Set in the Eastern Cape during the COVID-19 pandemic, the story centres around Litha (played by Liyabona Mroqoza), a young girl with a huge love of wildlife and family – something that becomes clear within the first few minutes.

Litha comes from a modest background. She’s raised by her father and grandmother, who – like many other families in the region – are hit hard by the pandemic. Tourism comes to a halt, and with that, any income her father had made carving wooden souvenirs. He tells her he has to leave home to find work but doesn’t say where. Litha’s grandmother, meanwhile, isn’t exactly thrilled with the girl’s independent spirit and tells her she’s “too wild to be under her hair,” pushing Litha to act on her own.

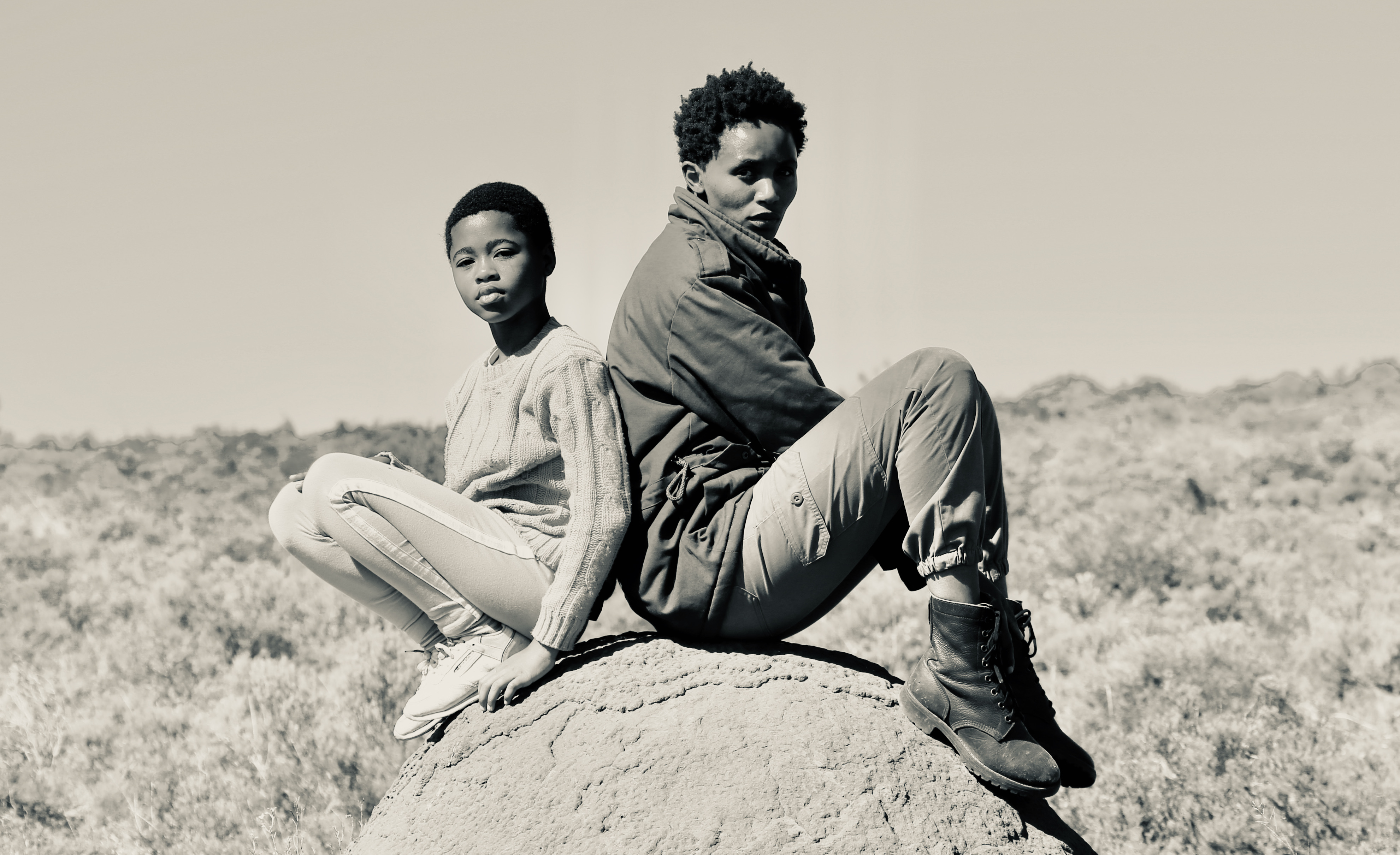

Wanting to help, Litha grabs her father’s wooden rhino carvings and heads out to a nearby lodge in the hopes of selling them. On the way, she bumps into Khuselwa: the last ranger still patrolling the area and monitoring the wildlife that remains. Litha quickly learns a harsh truth: the lodges are closed and won’t be opening anytime soon.

Seeing how disappointed she is, Khuselwa invites her along on a ride to see real rhinos in the wild – an offer too tempting to refuse.

Khuselwa and Litha connect pretty quickly as they ride across the landscape in her jeep. Their relationship feels open and honest from the start. Litha’s never used a video camera before, so when Khuselwa flips the screen and she sees herself for the first time, it’s a sweet, innocent moment that really captures her childlike wonder.

As they drive through the bush, Litha is wide-eyed while taking in all the wildlife around her. She learns the English word for “giraffe” and even sees a rare white rhino up close. One of the rhinos, Thandi, is familiar to Khuselwa. The two women keep talking as they sit in the jeep near her, with Thandi quietly listening in and just going about her day.

Things take a sudden turn, though. Thandi starts acting strangely – almost like she’s dancing – which is when it hits Khuselwa that something’s not right. The calm moment quickly shifts into something more serious, and now it’s up to Khuselwa to protect both Litha and Thandi from whatever danger is unfolding. What had started off as a beautiful moment turns into something much darker when poachers show up and suddenly throw Litha and Khuselwa into a life-threatening situation.

The Last Ranger is a powerful reminder that so much of what we encounter today – like safaris and the concept of poaching – didn’t just appear out of nowhere. These ideas really took shape when colonisers came in, took over the land, and disrupted how communities had lived with nature for generations.

Before colonisation, hunting was a way of life for many African communities – whether for food, cultural rituals, or simply to live in balance with nature. Once colonial governments took control, however, they introduced “preservation” laws that made it nearly impossible for local people to hunt on their own land. Suddenly, what had always been a way of life was deemed illegal. Colonial powers, meanwhile, were free to hunt for sport, sell animal products, and create luxury safari industries. So, what was once normal and necessary became “poaching” – but only when done by locals.

Fast forward to now, and not much has changed. Many of those colonial laws are still in place or only slightly rebranded. Conservation efforts still too often ignore the people who actually live closest to wildlife. On top of that, governments in many regions don’t provide proper support or alternatives – especially during hard times like the COVID-19 pandemic when tourism (a major source of income) dried up. So, for some people, poaching becomes a means of survival: not because they want to harm animals but because they’re left with no other choice.

“Poverty can betray even the deep love we have for animals and our own communities.”

Peter Egan, actor, conservation advocate, and Helping Rhinos patron

At the same time, rangers – like Khuselwa in the film – are stuck in the middle, trying to protect wildlife but often underfunded, under-protected, and at serious risk not just due to wild animals but also armed poachers and organised crime groups that see wildlife as profit. Many governments don’t invest enough in enforcement, anti-poaching programs, or efforts to track down and hold powerful poachers and trophy hunters accountable.

That’s the real issue here: the whole system still favours outsiders. Westerners can fly in, pay huge fees, and hunt endangered animals under the banner of “conservation” or “sport.” Meanwhile, the people who’ve lived with and respected these animals for generations are criminalised if they try to fish or hunt for food.

In the end, this isn’t just about wildlife – it’s political. The term “poaching” itself has colonial roots, the practice used to strip local people of their rights and justify the takeover of land and animals by outsiders. Colonisation and poaching are tightly connected, and unless we begin addressing that same history, the same old power dynamics will continue to shape conservation but with new branding.

Back in 1973, 80 countries signed an agreement called the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (“CITES” for short). The goal was to control and limit the international trade of endangered animals and plants. From the beginning, some African species, like rhinos, were already on the protected list.

Fast forward to 1990, and African elephants were officially added. That meant trading ivory for commercial purposes was no longer allowed, which had a massive impact: ivory poaching dropped off fast and became more manageable. The same couldn’t be said for rhinos, unfortunately, still heavily targeted by poachers ever since.

Beyond those big international moves, powerful grassroots efforts took shape across Africa. Take Helping Rhinos, for example, this group playing a big role in founding The Black Mambas – the all-female anti-poaching unit that inspired The Last Ranger. Their story really resonates with rangers like Khuselwa and many others on the front lines.

“I would die to protect wildlife.”

Sergeant Felicia Mogakane, member of the Black Mambas anti-poaching unit

Community-driven projects also focus on transforming former poachers into protectors of wildlife. John Kasaona, a key figure in this space, works in Namibia to help set up community conservancies (protected areas run by locals). He discusses how many people in his region used to poach just to survive, either to eat or earn money for their families.

When Kasaona spoke at TEDx, he shared a bit about his own background. He grew up under apartheid, with only white citizens allowed to hunt, farm, and use natural resources. Anyone Black who tried to do the same was labelled a poacher, fined, or thrown in jail. As he put it, “We were not regarded as responsible enough to use wildlife.”

Kasaona’s approach? Hire the people who know the land better than anyone (former poachers) and show them how wildlife can actually benefit their communities, a true game-changer in Namibia.

The Last Ranger helps shine a light on how international laws like CITES team up with local efforts to fight poaching. Stopping poaching in Africa isn’t just about laws, however, but also comes down to creating real opportunities and respect for the people living alongside wildlife.

In the end, it’s about balance. Protecting animals and supporting communities is the only real way forward, tasking us with ensuring both people and wildlife can live side by side safely.

Share: