Capetonians are notorious for waking up late to secure tickets for performances they want to see or needing serious motivation to attend an event not on their doorstep. Unless musical royalty like Malian kora player Ballaké Sissoko and South African guitarist Derek Gripper are in town. Their Baxter Theatre shows quickly sold out, as did their Market Theatre Joburg bookings, warranting an extra show added to the schedule. Durban fans also came out in support. “It’s quite remarkable. I feel very moved that people have responded as they have,” says Derek.

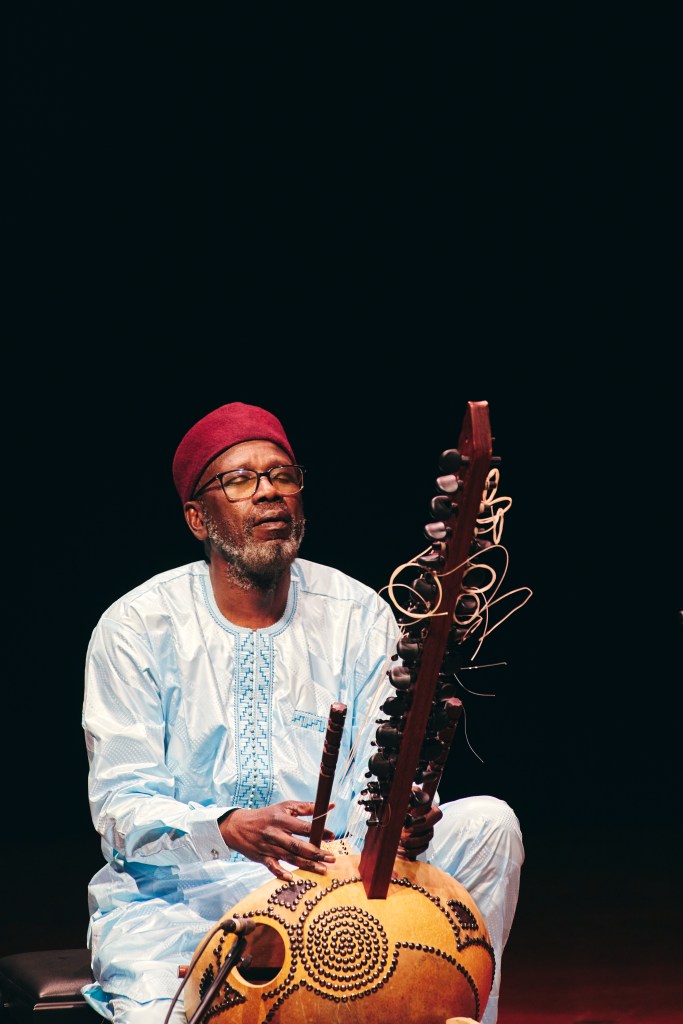

Ballaké Sissoko playing at the Baxter Theatre – Image credit: Lambro Tsiliyiannis

Derek Gripper playing at the Baxter Theatre – Image credit: Lambro Tsiliyiannis

Their first South African tour, on the back of concerts in the US, Turkey, France, Switzerland, and Sweden, was a resounding success and a reminder of the power of music as a universal language. “Ballaké literally speaks zero English. We use Google Translate to determine what time to meet in the hotel lobby,” quips Derek.

In essence, their dialogue is between instruments. They don’t discuss music, what they will play, or which key. “We go on stage, and somebody starts, and the other person follows. We have a shared knowledge of the griot repertoire, from old compositions to more modern ones, and we have a shared language for improvisation, learned from the ancient songs of the Mandé Empire. Every time we play together it is different,” he says.

They don’t have post-mortems either. What better way to nurture a brilliant musical career with no potential for argument? “The trick is always to forget the night before and start afresh the next day; Ballaké is a master of this. I have learned a lot from his approach to making music: he goes on stage as though he is going to sit there knitting a scarf, and then produces the most sublime music. He’s there to practice a craft. There is no separation between the performance and his day-to-day playing. This means that performances remain as living events,” says Derek.

Ballaké’s official name is Djelimoussa – Musa the griot. He belongs to the lineage of griots, hereditary musicians who pass on their skills and knowledge orally. Griots are musicians, historians, advisors, and wordsmiths.

According to legend, the first jelis date back to the time of the Prophet Mohammed. They played vital roles in the courts of the Mande people, who ruled powerful African empires from the 11th century onwards. Some of their repertoire dates to Sunjata Keita, founder of the Mali empire in 1235, or even earlier.

Ballaké’s father, Djelimady Sissoko, was a brilliant kora player born in Gambia, southern Senegal. Ballaké grew up playing the 21-string West African harp, learning by ear and practice, often skipping school to do so. When his father passed away in 1981, 13-year-old Ballaké took his place in the ensemble, becoming its youngest member.

Meanwhile, Derek was inspired by the kora. He transcribed and recorded significant kora works, including Ballaké’s, transforming classical guitar repertoire. “My contribution is to interpret music that existed in one tradition and one instrument and create the idea of Ballaké being a composer like celebrated European composers. This does two things; it reminds us that composers come from Africa and rehabilitates the idea of a composer who has become stilted and disconnected from actual playing practice, the craft of the hands.

“The transcriptions that I made 10 years ago were my way of learning the music. In the process, I learned that there’s a lot about it that defies having a concrete version. It’s kind of a memetic language that’s shared amongst all the musicians, and all the people there really. The music lives, so it changes, and the very idea of having a fixed score is kind of against its nature.”

The pair first played together at an event in London to mark 50 years of kora studies. Their spontaneous set proved so successful that they recorded their debut album – again a series of improvised encounters – at Platoon’s London the following evening.

“Musically, we tested each other,” says Ballaké, explaining that spontaneity is the most magical aspect of their encounters. “We have the mastery of our instruments, the technique and a good ear. Derek is very curious, that’s very important.”

Derek responds, complimenting Ballaké’s listening skills. “He’s such a good listener. It’s not what he plays, it’s how he plays it. He’s an amazing interpreter, the prime master of timbre. For me to play with Ballaké is to play with one of the great composers of our continent. It’s as though somebody called me up and said I had a gig with Bach.”

Derek calls their collaboration “a game of musical communication” through which they build a language of music together, enabling them to learn each other’s character. “Ballaké learns how I like to disrupt things, and he masterfully goes with that flow. I learn to listen carefully. There is so much wealth in paying close attention; you don’t have to go far to find something new.”

Rather than succumbing to the World Music label, if their music must be categorised at all, listening to it is instead otherworldly. “We are solo acoustic performers playing quiet instruments that need the audience’s full attention. And we have made our careers in a world where music is divided into categories, in our case, World Music, where performance contexts prefer big ensembles that can make a loud noise (Africa is always the party music). We represent a different vision of African music, as chamber music, as intimate music, as the music of speech between friends. So, we have both continued to honour the nature of our respective instruments, finding contexts where the instruments work best, and never changing the nature of the instrument, or our playing, to fit the music industry,” says Derek.

Derek’s transformation of the guitar with the kora in mind, reflecting two decades of dedication to a craft rich in history and wisdom, makes these African string sessions unique. “We’ve been able to do something that’s actually very different to what’s normally done on the kora. One of the reasons for this is that Ballaké has a new kind of kora that allows him to change the key in a second compared to 10 minutes on the old traditional koras. That has allowed us to explore tonalities and sonorities that you won’t hear in traditional kora music. Another is that we’re both improvisers, not in the sense of someone taking a flashy solo, but as storytellers. We both like to tell stories with music, going from one memory of a piece into a recollection of something that maybe never existed, then moving into this stream of consciousness, memories of pieces we both know, creating pieces we don’t know, him playing something I’ve never heard and reacting to that – there’s a kind of narrative that continues. In the more traditional pieces, you’d stick within the structure of the original piece and elaborate on that in a very small way. In the nineties, Ballaké recorded an album where you can hear a kind of contemporary improvisation going on – melodic but keeping within the structure of the piece. We’ve broken out of that structure.”

Images above by Lambro Tsiliyiannis

Lead/Main image by Hugh Mdlalose

Share: